Violence Risk from Chicago's Far Left: A Social Science Perspective

Radicalizing fringe groups are cause for concern – as are characteristics of Chicago Teachers Union militants and Mayor Brandon Johnson’s administration.

. . .

Takeaways –

1) Social science can help sort through impressions of extremism and abnormality among Chicago’s present-day far left.

2) Multiple factors identified by scholars at large suggest that the current situation is relatively troubling.

3) Some scattered fringe groups appear to be radicalizing into more and worse violence.

4) The mounting failures of CTU’s CORE caucus and the allied Brandon Johnson administration actually increase the risk of violence. That heightened risk will likely last while they tenuously hold power and during any post-defeat regrouping period.

. . .

. . .

Although few are happy with either, many people love to endlessly discuss the state and fate of the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) and the interlinked administration of Mayor Brandon Johnson. A June 2024 Economist article encapsulates major continuing tendencies: entitled “No promised land,” it emphasizes how Johnson’s “far left” politics face strained city coffers and distrustful state and federal partners, conjuring up the specters of broken promises, frustrated constituencies, and a slow-motion one-term trainwreck.[1]

However, striking details in roughly contemporaneous April 2024 coverage of CTU state lobbying efforts suggest a little something more might be going on than the Economist’s “insurgent politicians” and stymied hardcore supporters. As reported, one lawmaker was targeted with a “plan of escalation” for more than a hundred people to confront her over a refusal to hold a hearing, while others received “angry and even threatening calls.” Indeed, although initiatives fizzle out all the time in legislative chambers, it seems unparalleled in recent memory for activist lobbying to elicit so much uneasiness.

Impressions are not automatically dependable, however; elite discomfort could actually just come from impassioned and necessary truth-telling. With these perceptions of odd and untoward behavior, then, it seems necessary to check in on the actors themselves. Here, Exhibit #1 was also reported by a major national newspaper: that CTU president Stacy Davis Gates told union members to “punch their principal in the face.” Confirmed by CTU but explained away as “figurative,” this comment was also mirrored by a second and less-popularized allegation, that talk reached that same principal that he faced getting his tires slashed. If faithfully related, this other remark is much less metaphorical, and suggests that Davis Gates could very well have sparked intimidation of an adversary.

At the very least, such pointed abnormality across multiple domains justifies asking an unusual but important question: how much of a violence risk is Chicago’s far left?

Although nationally the far right is the greater threat, local radicalization can occur among other groups, and, indeed, when carefully diagnosed vis-a-vis known risk factors, the situation in Chicago is surprisingly troubling.

For any inquiry like this, it is essential to engage social science insights about why broader movements and particular organizations turn violent. Treating everything from “terrorism” to “new religious movements” (popularly known as “cults”), this polyvocal scholarship provides numerous lessons learned from past cases.[2] Because social phenomena are complex, these lessons do not outline fixed patterns and paths, nor can they indicate the certain future of any given group.[3] Rather, they highlight notable organizational and behavioral characteristics that can lead to violence and its escalation.[4] And, since press coverage and writings from the groups themselves are the building-blocks of many case studies, Chicago’s current political landscape easily permits equivalent evaluation for any such characteristics and trends.[5]

For such an inquiry to even begin, however, further clarity is needed around key terms like “violence” and “political landscape.”

First, useful distinctions exist between “militancy” and “violence,” as well as between various forms of violence. Although groups do not undergo any preordained evolution, “militancy” should be distinguished from “violence,” the former being a background of rhetoric and ideology consistent with violence, the latter concrete physical actions that are consistent with and emerge from militancy, although not necessarily so.[6] For example, Davis Gates’s alleged remark about face-punching constitutes militancy but not violence, since it is not an actual assault. “Violence” itself has been helpfully defined as damage to property or persons – for example, actual tire-slashing or actual face-punching.[7] Violence can also be further broken down in terms of target-types, the most relevant of which are “selective violence” (against individuals whose particular behavior renders them adversaries) and the more-indiscriminate ‘categorical violence” (against members of an enemy class).[8]

Second, with “political landscape,” boundaries get blurry. Is Chicago’s “far left” the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators (CORE) that’s currently in charge at CTU, or the United Working Families (UWF) group in which it participates, or the Brandon Johnson administration that both helped put into power, or is it even co-travelers from the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) whom this mayor advances and relies upon? Here, an important concept most at home in the study of new religious movements and rightwing extremism is the sociological framework of the “cultic milieu,” perhaps better termed the “milieu of oppositional subcultures.”[9] Basically, every society has a center of accepted beliefs and practices. Then, at increasing distance from this mainstream there lies a jagged subcultural fringe of cultural fermentation – that is, a variegated, creative space where innovations pop up and flow into each other and mix, sometimes petering out, but at other times percolating out into the broader culture, whether for acceptance there or for subsequent recession back to the periphery. Within this milieu, organizations and affiliations come and go, as people travel among many interconnected corners of this universe and adopt and nurture novelties. Thus, what’s most important isn’t individual organizations per se, but rather the unusual and innovative views and practices, especially those that are getting solidified, disseminated, and mainstreamed. Think, for example, of how the marginal cause of police abolition became more prominent in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, or how the 2023 Hamas attack catalyzed activism around Palestine and led a DSA-affiliated Chicago alderman to appear alongside even-more radical leftists, first at an event with a flag-burning, and then at a protest planning meeting where “Death to America” was chanted in Farsi. More than news story sensationalism, these glimpses of a ragtag subcultural panoply with boundary-pushing ways that might birth something bigger are fully expected, sociologically.

Accordingly, analysis of Chicago’s “far left” should encompass everything from certain labor unions and associated politicians through such far-flung fringe groups. Of course, the labor and political entities are comparatively unremarkable, with the important caveat that they can help mainstream nonstandard ideas. Conversely, although “guilt by association” and emphasis on abnormality can form political playbook smears, the more-peripheral oddities of the so-called “loony left” are intellectually obligatory to examine, when evaluating violence risk across these social strata. Indeed, such an examination does not essentially differ from journalistic and community scrutiny of rightwing radicals’ inroads into the Chicago Police Department, from the same concern about vectors of spreading extremism.

All that said as preface, one simple fact must be immediately acknowledged upfront: according to scholarly definitions, low-level violence has already been emerging from Chicago’s far left.

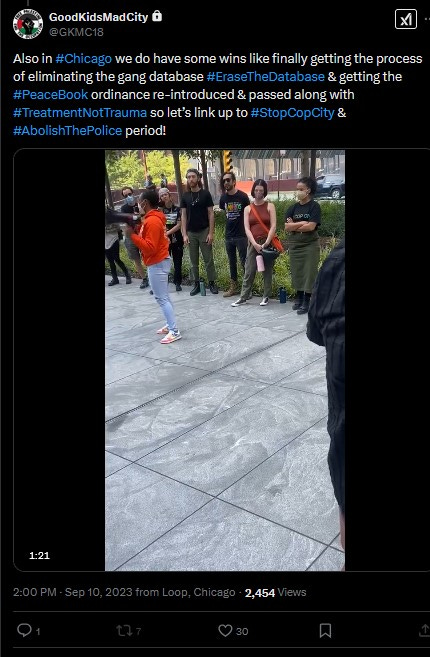

Mostly undertaken by very outer fringe groups, this sporadic low-level violence has fit into broader national trends around property damage during or as protest. For example, Buckingham Fountain suffered vandalism featuring “Stop the genocide” graffiti, and a University of Chicago building was occupied by a “Bring the Intifada Home” group that abruptly confronted former Senator Heidi Heitkamp and ordered her to vacate her office there. A lesser-known 2023 incident also featured “Stop Cop City” and “Fuck RICO” graffiti, suggesting that local activists vandalized several Chicago businesses out of solidarity with a multifaceted Atlanta protest occupation whose advocates have faced racketeering charges over arson and other alleged acts.[10]

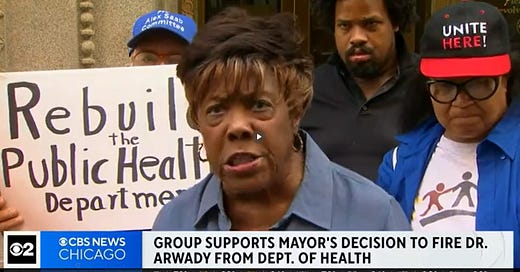

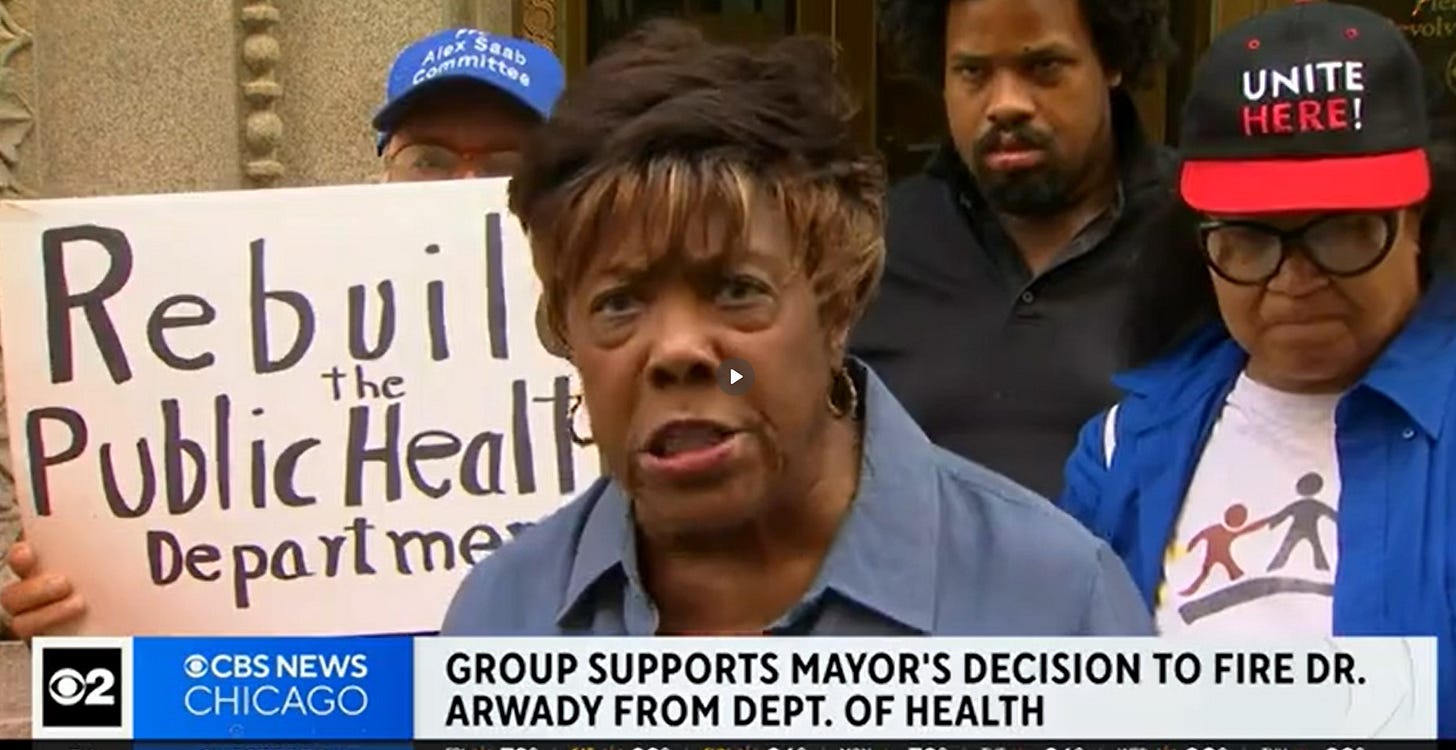

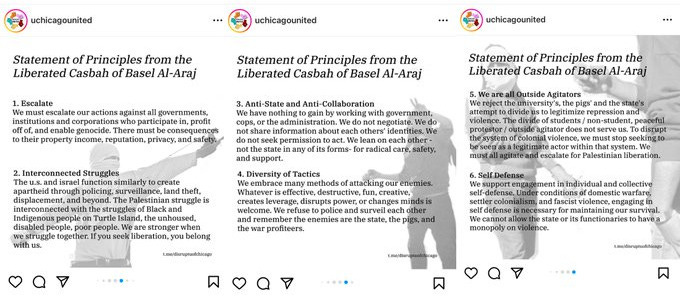

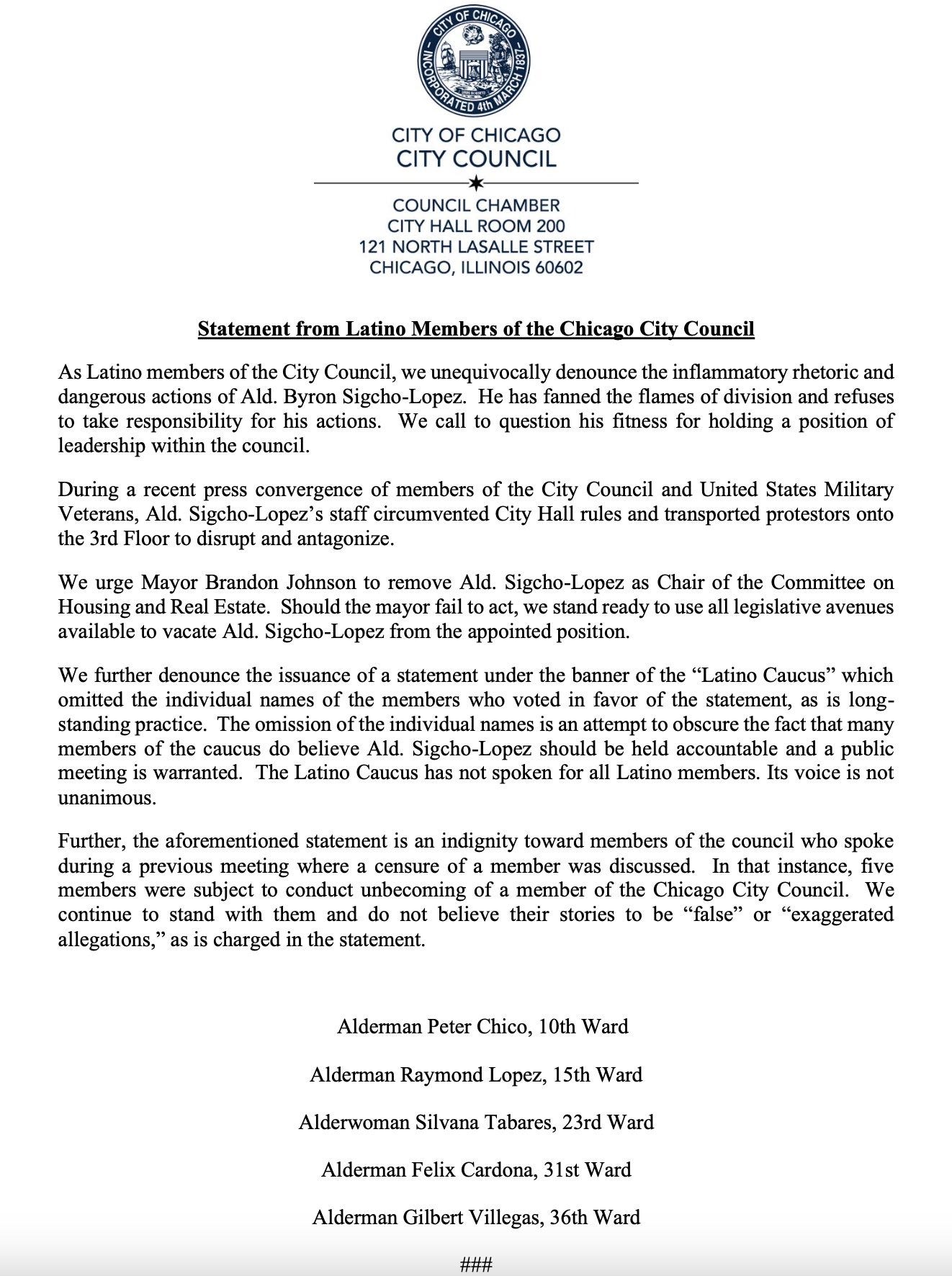

Occasionally floating around the Johnson administration and its allies, such smaller and scattered groups present worlds in themselves to analyze, although they are relatively more inaccessible and can lack robust paper trails. For example, at a 2023 blitz protest in favor of Johnson’s infamous 2023 firing of respected public health commissioner Allison Arwady, a “People’s Response Network” activist was caught on camera wearing a strange baseball cap referencing Alex Saab – namely, the brief leftwing cause célèbre who was an accused money launderer for Venezuela’s authoritarian Maduro regime. Although most in the news for their laudable advocacy to increase opportunities for youth – something for which they have been rightly praised by Johnson – the Good Kids Mad City group also bridges into the more outré police abolition and “Stop Cop City” activism.[11] Whether ephemeral or more-established, however, such subcultural groups present a problem of insufficient information: you don’t know quite who’s involved in them or what else they might be up to or where they might be headed, whether directly or in collaboration. That “major question mark” becomes more concerning because of the violence already present in these circles. Most pointedly, the spring 2024 UChicago building takeover group even explicitly endorsed that approach, reportedly writing that “We cannot allow the state or its functionaries to have a monopoly on violence,” while a fall 2024 attack on two Jewish DePaul students could have originated with another such strategically-violent protest group, although assailants have not yet been identified nor any responsibility apparently claimed.[12] To add concern upon concern, five alderpersons have also alleged that another’s staffers helped miscellaneous protestors breach City Hall protocols and ambush a press conference.[13] Although unremarked on in the press, a photograph documents how t-shirts of those protestors advertise not only a SEIU local, but also the explicitly revolutionary and politically quite bizarre Party for Socialism and Liberation. During such a guerilla protest or when face-to-face with the unwitting target of a building takeover, what would happen if a fringe participant took violence farther than property damage?

Beyond this more-purposeful low-level violence and the horizons that opens up, one other incident also deserves mention – how after her failure to make the mayoral runoff in 2023, an erratically-behaving man confronted police about their continued presence outside then-Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s home. Hazily evincing distorted concerns over excessive police funding, the man’s reported actions also seem like nascent categorical violence, wherein extreme political rhetoric against then-Mayor Lightfoot as well as law enforcement probably encouraged some sort of off-kilter cathartic challenge towards both. Frequently dismissed as “lone wolves,” such actors actually arise from interpersonal networks of ideological formation and behavioral encouragement, including as the end-result of “stochastic terrorism” (that is, when political demagoguery and its social media amplification sparks plausibly-deniable third-party violence).[14] To incorporate this other dynamic, then, both extreme fringe groups and any such unhinged individuals become perceptible as general violence risks – especially when receiving affirmation and even assistance.

Thus too comes into focus what is perhaps the most unexpected source of violence risk on Chicago’s far left – the radicals of CTU’s CORE caucus. As is well-known, a reform caucus that coalesced in the late 2000s eventually won power in 2010 union elections under the leadership of the much-loved Karen Lewis.[15] However, right at the moment in 2014 when CORE and CTU began seeking greater involvement in electoral campaigns, Lewis was sidelined by and ultimately succumbed to cancer, triggering a quiet but historic change: CORE leadership passed on to a hardline and relatively authoritarian faction that included the next CTU President Jesse Sharkey, current President Stacy Davis Gates, and others like Jackson Potter.[16] With this ascendent cadre, less-publicized fringe affiliations sociologically suggestive of participation in and open channels to further radicalism abound. Most prominently, Sharkey spent decades with the explicitly revolutionary International Socialist Organization (ISO) – a group that infamously imploded due to a disputed “rape coverup” in which CTU communications staffer and fellow ISOer Eric Ruder allegedly took part.[17] Beyond ISO, fondly-remembered founding CORE member and CTU organizing coordinator Norine Gutekanst has been claimed as a member by the revolutionary group Solidarity, while Jackson Potter’s mother was apparently part of a “Revolutionary Student Brigade” in her waning law school days in Iowa, prior to her move to Chicago and the controversial lawsuit whose settlement on behalf of CTU netted her and another attorney millions.[18] Currently, this hardline cadre partners via UWF with the less-scrutinized SEIU Healthcare leaders Greg Kelley and Erica Bland-Durosinmi, and it continues to prioritize using union dues and perhaps other money for high-stakes electoral gambits. Yet, an important post-Lewis schism has arisen and birthed a rival to CORE: politically similar in many regards, the competing Respect - Educate - Advocate - Lead (REAL) caucus now campaigns around transparency, democracy, and tolerance for dissent. Specifically, top issues include CORE’s failure to publish mandated financial audits and its increasingly unchecked leadership, who allegedly abuse authority, manipulate meetings, and attempt to silence dissent through “insults, bullying, [and] fear of retribution.” Quite interestingly, too, just like Democrats claim Lincoln from Republicans or Luther claimed Jesus from Rome or Freezone Scientologists claim L. Ron Hubbard from David Miscavige’s ecclesiastical behemoth, this newer and quasi-schismatic REAL caucus also claims Karen Lewis as a figurehead, in an effective accusation that today’s CORE has sold out its beloved founder.[19] Thus, just like its allied Johnson mayoral administration, CORE has also been facing a significant uptick in discontent.

Quite counterintuitively, however, CORE’s increasingly troubled position actually indexes to a greater risk for violence.

Why?

At least four major factors identified in social science research are at play.

First, there’s what some literature confusingly terms “upward spirals of political opportunities” – that is, when circumstances allow a group to successfully move to ‘the next level,’ but its old strategies cease to work and it must locate new ones.[20]

Concretely, this would consist of how CORE must now not only defend the increasingly unpopular albatross of the Johnson administration, but also fight for seats in the new elected schoolboard – all very costly endeavors for which much money and member commitment is necessary.

Second, there’s what some literature identifies as “competition for power” – that is, when a contending group edges in on the base of the group in question – as well as a closely-related winnowing effect, where doubters and internal opposition exit and remaining adherents become more and more extreme.[21]

Concretely, this would consist of how the quasi-schismatic REAL forms an easy and likely permanent offramp for dissatisfied CORE members, steadily depriving CORE of not only that support, but also that group-internal counterbalance, leaving the beleaguered CORE ever more unmoored under its harsh and erratic leadership.

Third, there’s the “commitment mechanism” of obtaining “cohesion” through marshaling members against an external foe – that is, of all the ways to keep people together, one prominent one is by hyping up a common enemy.[22]

Concretely – and this deserves a much longer analysis – although maintaining support with everything from red t-shirts to good contracts, CORE disproportionately and rather distinctively relies on internal bonding through extreme vilification of a rotating cast of opponents – something easily seen with a recent controversy over group-internal insults directed at Chicago Public Schools CEO Pedro Martinez.

Fourth, there’s the peripheral presence of millennialism-like ideologies wherein believers likely conceive of themselves as historic world-changers with a “sacred mandate” to gather others and face down severe social pushback and usher in a new era – a self-conception that makes the prospect of project failure harder to tolerate, and could incentivize innovations towards ideologically permissible violence in the present.[23]

Concretely, these are the varied, explicitly revolutionary socialist ideologies visible around a subset of CORE members and allies – for example, the thinking of Sharkey’s ISO, that workers need to increasingly formally coalesce as a prelude to conflict with the state and ultimate widespread revolution. To the extent that some CORE members or allies see themselves and their vehicles like UWF as beginning to fulfill these quasi-messianic roles that conceive of inevitable albeit distant violence, any impending major setbacks would likely strike such a subgroup incredibly hard and increase their desperation and volatility, above and beyond factors facing the group as a whole.

Cumulatively, these factors highlight how the already-militant CORE needs resources like a big engaged membership more than ever, but they’re working with less, and they’re thus more likely to rely on violence-producing strategies. CORE’s leadership, its schoolboard candidates, and its mayor are all increasingly tougher sells, while unfavorable factors like strained CPS finances are hindering less-objectionable strategies like providing a fat contract. Conversely, CORE can easily provide trumped-up villains, including around larger social causes. As a paradigm for when traditional success becomes increasingly uncertain, think of how one DSA alderman allegedly manhandled another in order to ensure a voting victory around a CORE-Johnson stance on migration: to make something work amidst very shaky circumstances, unexpected and quite erratic events begin happening. In light of the extremists already visible on the fringes of Chicago’s far left – fringes to which CORE and its allies have any number of links, and some far parts of which already practice and openly avow violence –any number of scenarios of violence against persons become conceivable, whether against rival candidates or against demonized individuals or against out-groups, whether by group members or by protest allies or by so-called “lone wolves.” Quite troublingly, within this subcultural thicket and its vague atmosphere of abnormality, delving into details and engaging relevant research does not allay violence concerns, but rather actually heightens them. If something like an attack on a person occurred tomorrow – something like may have already happened at DePaul, or worse – 95% of the story would already be written, and it would merely be a matter of figuring out the actor backstory and where and how it slots into the larger known developments.

Of course, no future is written in stone, but heightened violence risk seems baked into Chicago’s far left for the foreseeable future. Most prominently, outer fringe groups seem to be radicalizing towards more and worse violence. Furthermore, additional risk exists while both CORE and the Johnson administration hold sway, as well as during any adjustment period following any loss of power. Ideally, in the short-term, CORE and UWF leaders would self-examine and step back from their practice and sponsorship of intense demagoguery, while, in the long-term, any disaffected militant members would forego violent fringe strategies and instead re-engage and re-socialize through more-stable political actors like REAL.[24] Sadly, however, the radicalizing outer fringe groups seem much more unreachable, volatile, and intractable. In any case, discussion of Chicago’s politics should start broaching these troubling and extremely underdiscussed issues of militancy, violence, and radicalization. Even amidst mounting failure and occasionally outlandish actors, something else seems growing, and it might be even closer than we think, during this unprecedented and surprisingly tumultuous period.

. . .

. . .

David Mihalyfy has a Ph.D. in Religious Studies. He has researched, taught on, and written about new religious movements. His analysis of use of racketeering laws against new religious movements and groups identified as “cults” is forthcoming in Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions.

. . .

. . .

[1] “No promised land,” The Economist (15 June 2024): 23. Quotes taken from print version of article.

[2] Regarding the navigation of this kind of polyvocalism, note Inger Furseth and Pål Repstad, “Social and religious movements, radicalization, and violence,” in An Introduction to the Sociology of Religion: Classical and Contemporary Perspectives, 2nd ed. (Abingdon, England: Routledge, 2024), 261: “It is a good idea for scholars to use a dynamic approach and combine elements from cultural, structural, political, and organizational perspectives, rather than focus on one singular perspective.”

[3] Eitan Y. Alimi, Chares Demetriou, and Lorenzo Bosi, The Dynamics of Radicalization: A Relational and Comparative Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 33. Sergio García-Magariño, Violence, Politics and Religion: A General Theory of Violent Radicalization (Oxford: Taylor & Francis Group, 2024), 17-18, 33, and 46n1. Note also a particular aside of Furseth and Repstad, Introduction to the Sociology of Religion, 264: “It can also be difficult to distinguish between conservative groups that might pose a threat to integration, but not to security and vice-versa.”

[4] García-Magariño, Violence, Politics and Religion, 17-18, 32.

[5] Furseth and Repstad, Introduction to the Sociology of Religion, 270-271.

[6] Alimi et al., Dynamics of Radicalization, vii, 11. Pace the advocacy for definitional inclusion of “non-physical injuries like psychological… and social injuries” by Furseth and Repstad, Introduction to the Sociology of Religion, 265.

[7] Alimi et al., Dynamics of Radicalization, 11-2.

[8] Alimi et al., Dynamics of Radicalization, 12.

[9] For the best introduction to this idea, see Jeffrey Kaplan and Heléne Lööw, “Introduction,” and the reprinted Colin Campbell, “The Cult, the Cultic Milieu and Secularization,” in Jeffrey Kaplan and Heléne Lööw (eds.), The Cultic Milieu: Oppositional Subcultures in an Age of Globalization (Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2002), 1-11 and 12-25. For consistent use of the more-appropriate “oppositional subcultures” terminology seen in the subtitle of the Kaplan and Lööw volume, see David Mihalyfy, “Heterodoxies and the Historical Jesus: Biblical Criticism of the Gospels in the U.S., 1794-1860” (University of Chicago Ph.D. dissertation, 2017).

[10] For this and other such prosecutions, see David Mihalyfy, “A Recent Trend of Racketeering Prosecutions and Civil Suits Against New Religious Movements and ‘Cults,’” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions (forthcoming).

[11] Per reporting, Johnson stated, “These are remarkable young people who want to participate in transforming our city, and so that type of participation and engagement from our young people is critical… We have to find ways to continue to support this effort because it’s going to take all of us to build safer communities.” Per a social media post documented and publicized on X (Twitter) (2:00pm on 10 September 2023), GoodKidsMadCity (@GKMC18) stated, “[L]et’s link up to #StopCopCity & #AbolishThePolice period!”

[12] Per social media posts documented and publicized on X (Twitter) by the Midwest arm of the Anti-Defamation League (@MidwestADL) (8:49am on 19 May 2024), the group responsible for the UChicago building takeover stated, “We cannot allow the state or its functionaries to have a monopoly on violence.”

[13] Per the social media post on X (Twitter) by Silvana Tabares @AldermanTabares (12:27pm on 28 March 2024): “During a recent press convergence [sic] of members of the City Council and United States Military Veterans, Ald. Sigcho-Lopez’s staff circumvented City Hall rules and transported protestors onto the 3rd Floor to disrupt and antagonize,” reads the statement signed by Alderpersons Peter Chico (10th Ward), Raymond Lopez (15th Ward), Silvana Tabares (23rd Ward), Felix Cardona (31st Ward), and Gilbert Villegas (36th Ward).

[14] Molly Amman and J. Reid Meloy, “Stochastic Terrorism: A Linguistic and Psychological Analysis,” Perspectives on Terrorism 15.5 (October 2021): 3-4; note also the penetrating observation that “the beauty of implicature is that it provides an escape when a speaker needs to cancel an interpretation by simply adding more content” (6). Molly Amman and Reid Meloy, “Incitement to Violence and Stochastic Terrorism: Legal, Academic, and Practical Parameters for Researchers and Investigators,” Terrorism and Political Violence 36.2 (2024): 235, 241-242. Alimi et al., Dynamics of Radicalization, 37. See also Brian Michael Jenkins, “The Atomization of Political Violence,” in Nicolas Stockhammer (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Transnational Terrorism (Abingdon, England: Routledge, 2024), 62, 66-67, and 69-70. Note, however, the caution of García-Magariño, Violence, Politics and Religion, 44: “Although virtual communities act as spaces for radicalization, physical communities generate more intense dynamics.”

[15] For standard narratives that relatively neglect key subcultural influences, see Steven K. Ashby and Robert Bruno, A Fight for the Soul of Public Education: The Story of the Chicago Teachers Strike (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016), 62-70; and Micah Uetricht, Strike for America: Chicago Teachers Against Austerity (London: Verso, 2014), 17-37 (though note a reference to “socialist political traditions” on 30).

[16] For example, Uetricht’s 2014 Strike for America tracks this emerging change, noting that “[t]he CTU has announced plans to wade into city politics” (132) and referring to “[t]his shift to electoral politics” (133).

[17] Per ISO Leaks, “Inside the International Socialist Organization’s Dissolution After a Rape Cover-Up,” Medium (11 April 2019, accessed 26 February 2025 at https://medium.com/@isoleakss/inside-the-international-socialist-organizations-dissolution-after-a-rape-cover-up-b954e354143), a “Post-Script” identifies Ruder as one of the “2013 ISO Steering Committee members who were complicit in the rape coverup.”

[18] Per Chicago Solidarity, “VIDEO: ‘Lessons from the Chicago Teachers Strike,’” Solidarity (4 October 2012, accessed 26 February 2025 at https://solidarity-us.org/p3707/), Gutekanst is “a member of the Chicago branch of Solidarity,” and the transcript of her remarks indicates decades-long membership beginning before 1987 (“I’ve been a member of the Chicago Teachers Union since 1987 but I’ve been a member of Solidarity even longer”). Gutekanst’s role as a CORE founding member is also mentioned by Jackson Potter and in Ashby and Bruno, Fight for the Soul, 62. Robin Potter, “The Shah, the Pres., and empty phrases,” Daily Iowan (16 February 1977), 4, in a letter signed “Robin Potter for the Revolutionary Student Brigade.”

[19] For example, see the reverence for Lewis on REAL Caucus for CTU, “OUR PLATFORM,” REAL: Respect – Educate – Advocate – Lead (accessed 26 February 2025 at https://www.realcaucus.com/platform): “Karen Lewis put it best when she said: ‘It all comes down to how you teach people to fight with the tools they have. We have been fighting with the bosses’ tools…That’s one tool. But it’s not the only tool. Our best tool is our ability to put people in the street. The tool that we have is a mass movement. We have the pressure of mass mobilization and organizing.’”

[20] Alimi et al., Dynamics of Radicalization, 42-43.

[21] Alimi et al., Dynamics of Radicalization, 45-46 and 46-47. David G. Bromley, “Deciphering the NRM-Violence Connection,” in James R. Lewis (ed.), Violence and New Religious Movements (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 23.

[22] For the classic formulation, see Rosabeth Moss Kanter, “Commitment and Social Organization: A Study of Commitment Mechanisms in Utopian Communities,” American Sociological Review 33.4 (August 1968): 499-517, particularly 507-510. Note also the applicability of Bromley, “Deciphering the NRM-Violence Connection,” 24, on loyalty tests, shifting goals, and the creation of new challenges for followers.

[23] Bromley, “Deciphering the NRM-Violence Connection,” 20-21, 23, and even 25 (regarding “permission for violence”). Furseth and Repstad, Introduction to the Sociology of Religion, 265. Note the similar case study observation of García-Magariño, Violence, Politics and Religion, 25, about how some ideologies need only admit “one step” towards “the justification of violence.”

[24] Alimi et al., Dynamics of Radicalization, 248-251. García-Magariño, Violence, Politics and Religion, 26.